Sangmi Yoo

Dazzle Dazzle 01, 2017, Photo lithograph, 19 x 27 inches.

“I am always surprised by the multitude of colors existent in the objects, beyond our stereotypical understanding of local colors.”

Sangmi Yoo is an artist living and working in Lubbock, Texas (USA). Her approach to color reflects personal and public environments, and her approach to printmaking involves an economy of layering colors. Sangmi’s architectural work simulates optical illusions in conjunction with tangible realities. She uses screenprinting, laser engraving and risograph printing, among other media, to create installations with constructed print panels that are hand-cut or laser-cut.

Sangmi’s current work focuses on botanical gardens and colonialism through prints and installations. This new work references the 19th century colonial botany of Latin America and how botany was utilized in investigating the resources within the region. She is working on a study suite of drawings from botanical gardens and science museums in the US and other countries, which will be used to create a series of prints that incorporates etchings, monotypes and layers of colors.

Are there specific associations towards color in your work?

Most of my colors are derived from architectural surroundings where my subjects are located. I take photographs of the houses, buildings, botanical elements, etc. Colors in the composition are variations of shades of colors extracted from the photographs.

I am always surprised by the multitude of colors existent in the objects, beyond our stereotypical understanding of local colors. Simulating the perception and a collective memory, I have developed my interest in American suburban housing development and the 19th century colonial botany existent in the public botanic gardens in the US.

The play of cast shadows and colored stripes in my works are developed from Dazzle (disruptive) camouflage patterns used in war ships during World War I. Dazzle ship camouflage used in World War I by a British marine Artist, Norman Wilkinson, makes it difficult to estimate a target’s range, speed, and heading. With the pandemic and the ever-changing political climate in global relationships in recent years, these patterns resonate the interferences and intersections being part of this tension.

By means of these choices, I focus on creating a sense of fragility in memories and in illusions of the world we believe. I am interested in the juncture of private space and public built environments, such as Botanic Gardens, stereotypical public places in the US and its territories, such as Puerto Rico. Cultural representations of botanic gardens are interesting and problematic as they embody many different histories and colonial perspectives still residing in our everyday life.

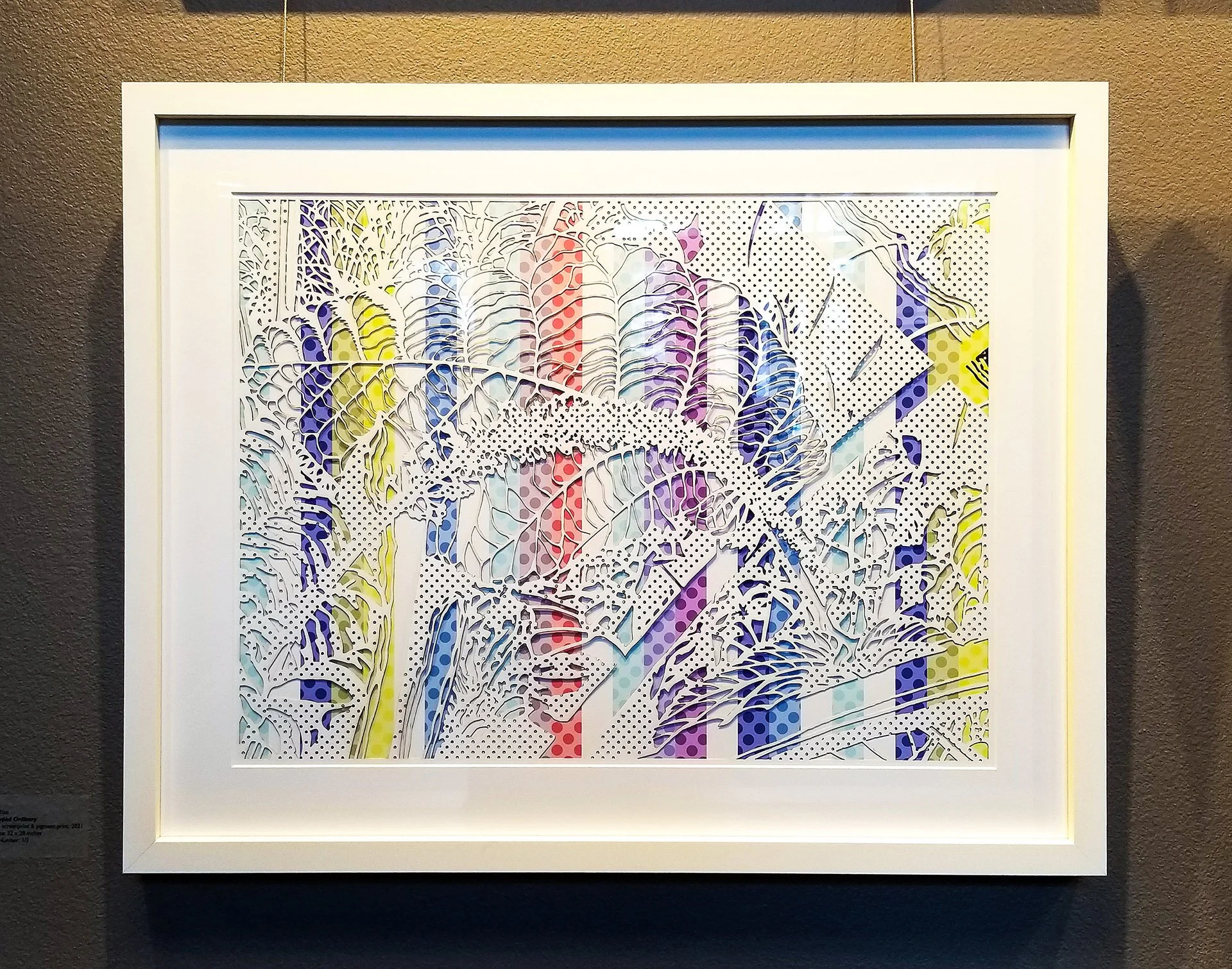

Dazzle Dazzle 03, 2021, Photolithograph, 27 x 19 inches.

Stereotyped Ordinary, 2019, Hand-cut pigment prints, 72 x 44 X 24 inches each.

Stereotyped Ordinary (Haiku Dazzle), 2022, Hand-cut pigment print, 96 x 44 x 12 inches.

“I try not to use black in my work to allow the viewer to mix the colors by their eye.”

How does the printmaking process itself relate to how you work with color?

Layering process in printmaking has given me a consciousness of achieving a complexity of colors by mixing a minimum of color layers with transparency. My interest in layering started with CMYK color separations early in my practice, but I diverted into secondary and tertiary color combinations.

I try not to use black in my work to allow the viewer to mix the colors by their eye. For instance, shadows created under my cut prints in installation are not different shades of grays, they are the effects of variety of light sources, direction of lights, and the amount of light penetrated through the paper.

Influenced by Josef Albers, Bridget Riley, and a strange hybridization between Korean Monochrome Painting and American Minimalism, my earlier work used reductive vocabulary and seriality. I still maintain the economy of layering of colors and pairings of prints while the effects are more complex associations of colors.

What cultural aspects of color are built into your work?

Even though I extract colors from the site photos I use as references in my work, the final selection of colors belongs to the five fundamental colors of a Korean tradition. For instance, Saekdong pattern of Korean traditional dress is a variation of these five colors. Korean ancestors believed wearing Saekdong provides their children a protection from evil spirits and deadly diseases. This belief about color combination came from a Shamanistic tradition but continued even after the dominant Confucius’ influence in the Joseon Dynasty and the arrival of Christianity in the late 19th century.

These five fundamental colors are called Obansaek. Saek means color in Korean. They are black, white, red, yellow, and blue. While it is not the same as the Western color mixing theory, mixing Obangsaek and adjusting the saturations creates a variety of secondary colors, called Ogansaek. The later designs of Saekdong dress reflect the mixture of Obansaek and Obansaek. They have been widely used in clothing, architecture, furniture, accessories, etc. see more information in this article

I was not intentionally using this Obangsaek and Ogansaek concept in my work at first, but I found my color bias towards this color scheme after observing my color palette from my earlier practice in 2007-2010. For me, it was such an irony since I was trying to avoid a certain stereotypical traditional Asian look in my work. I finally became more comfortable embracing the natural inclination towards the color scheme rather than fighting it.

As I continue with my practice, I have become more freed from the restriction of this palette by deviating from the strictly extracted colors from my subjects. I also learned ways to create a variety of values and intensity of colors to simulate dark colors close to black without using it. However, it is interesting how my color choices are resonant of my upbringings and visual surroundings from my childhood.

Stereotyped Ordinary, 2022, Layered lasercut screen and inkjet print, 22 x 28 inches.

Tides of Resilience, Installation view at NorthPark Center, Dallas, TX, 2022, Hand-cut pigment prints, Dimensions Variable.