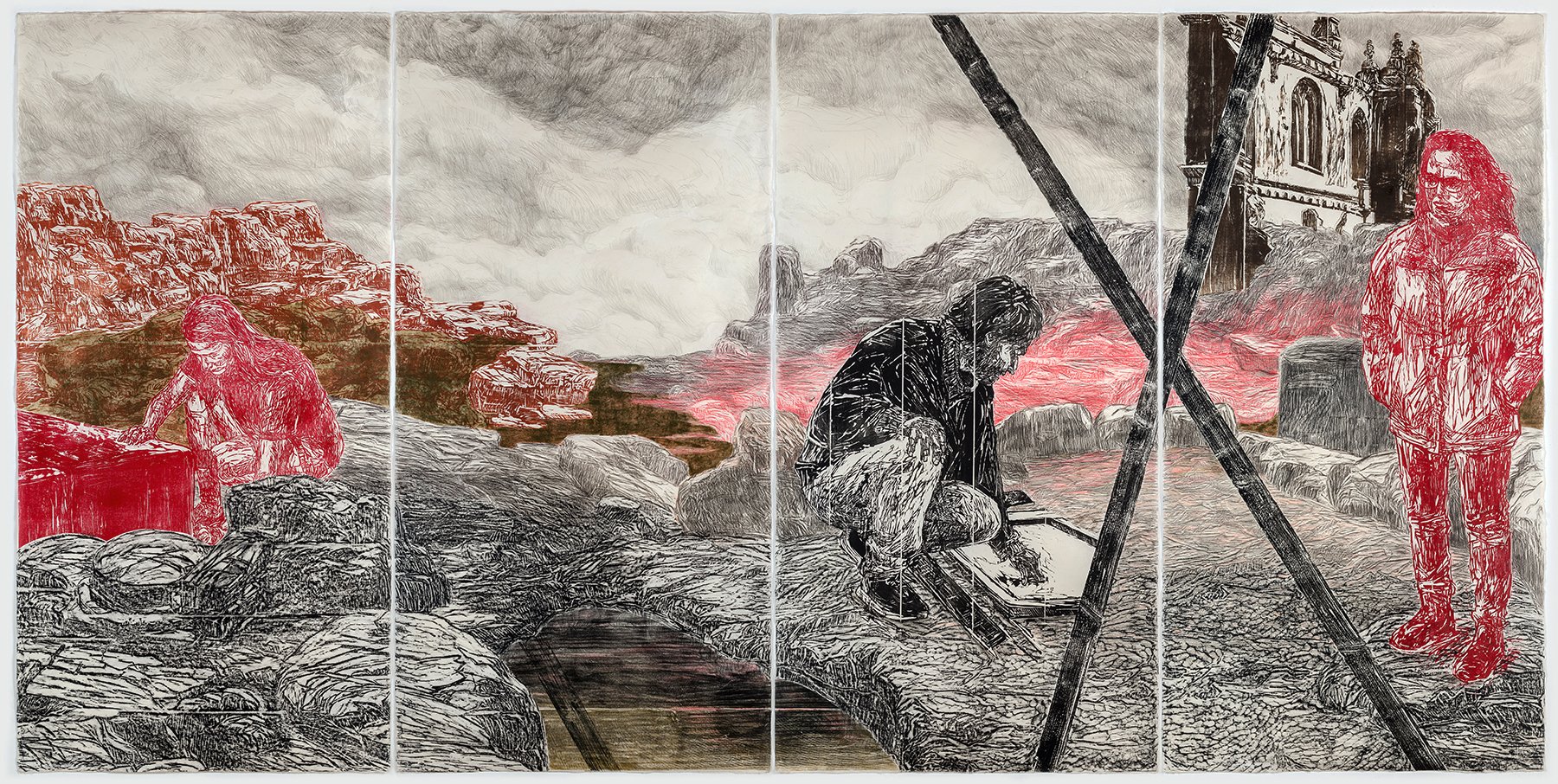

Orit Hofshi

Cistern, 2022, Woodcut, rubbing, color pencil, on handmade Kozo and Abaca paper, 80 x 40 inches.

“...possibly, for many years, including color deliberations felt practically a distraction.”

Orit Hofshi is an artist living and working just north of Tel Aviv (Israel). Her approach to color has been very particular, while recently becoming bolder. She is a passionate scholar of printmaking traditions and the great masters, and she also explores a combinatorial and non-conventional approach to printmaking.

The specific vocabulary of mark-making in Orit’s woodcuts is created through hands-on methods of relief printing and frottage printing, techniques which are also significant to both the personal and creative themes in her creative practice. Her work also incorporates handmade paper, full-scale installation, and sound.

Currently, Orit’s work is on view in the upcoming exhibition “The Anxious Eye: German Expressionism and Its Legacy” at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. (11 Feb–27 May, 2024). Orit will speak about her work at the exhibition on 23 March, 2024. She is also mounting a solo exhibition at Yossi Milo Gallery in New York City, which opens on 14 March, with an opening reception on 21 March, 2024.

Nebulous, 2022, Hand printed woodcut, rubbing, pencil drawing, ink, on handmade Kozo & Abaca paper, 80 x 160 inches.

How much does color play a part in your art?

Much of my work for a couple of decades was primarily quite monochromatic, and not solely because I am probably not a natural colorist. My work is typically very intense and quite physically demanding. The direct hands-on process includes gluing pine wood boards, creating very large panels, drawing on the boards, carving and manipulating the temperamental pinewood, and then gradually spoon-pressing the large paper sheets. I feel every phase is virtually an independent creative stage in its own right. So possibly, for many years, including color deliberations felt practically a distraction.

Moreover, I felt the woodcuts were quite colorful all along! Combining a wide range of manipulations when carving, while also embracing distinct pinewood characteristics in the process. This is both a natural extension of my dialogue and respect for wood as a resident of our environment, as well as the realization creative inclusion of wood patterns can often enhance the woodcut dramatically.

Spoon printing enables both selective and specific areas of pressure as well as the use of varied amounts of ink. So even while using a single color ink, the print effectively displays a noticeable color spectrum, from dark to very light shades of color, densely printed patterns to hardly visible brush scratched patterns on the wood, and so on. My color range at the time did vary from black to deep blue or raw amber to name a few, applying the selected ink exclusively on the entire board.

“So even while using a single color ink, the print effectively displays a noticeable color spectrum, from dark to very light shades of color, densely printed patterns to hardly visible brush scratched patterns on the wood and so on.”

Steadfastness, 2010, Woodcut on handmade Kozo & Abaca paper, 68 x 141.3 inches.

For a decade now, my work has included a broader color pallet, corresponding, perhaps, to my also incorporating multiple printing methods and drawing as part of my creative process. The integration of color in my works has been gradual, contemplative, and neither necessarily realistic nor figurative nor decorative.

I do not observe particular medium paradigms or conventions, i.e., woodcut traditions or common scale, as my creative compass or agenda. This is not just in terms of the complexity and depth of technique and color use in woodcutting, rubbing, and drawing but as a reigning philosophical state of mind – various media and innovative techniques are the toolbox in the creative process.

Interval, 2020, Woodcut, rubbing, color pencil, on handmade Kozo and Abaca paper, 80 x 132 inches.

Over the years, I have been intrigued by the work of a couple of woodcut masters, each using color in their own remarkable way, and both notable in their expressionist sentiments. Edvard Munch’s brilliant, stirring, deceivingly straightforward, quite figurative colored woodcuts have been an entrancing beacon and stimulant.

My transition from one-colored woodcuts to multiple-colored prints had been gradual, as I mentioned earlier, and was undoubtedly inspired by Munch’s work, even if I did not share his comprehensive conceptual and philosophical mindset. I have been fascinated by Munch’s bold, intellectual, and spiritual journey as an artist, admiring his passion and innovation.

“The expressive, nonrepresentational use of color and the delineating interlocking forms by color seek to enhance the sense of alienation and displacement, questioning the relationships within and between humankind and the natural world.”

Withdrawal, 2023, Woodcut, rubbing, color pencil, on handmade Kozo and Abaca paper, 52 x 70.1 inches.

Munch exercised liberty in consciously using colors corresponding principally to feelings or imagination rather than to naturalistic realities. His using color to elicit emotional reactions from the viewer, taking precedence over accurately depicting the world around him, was a radical approach in his time. Granted, his choices reflected Victorian beliefs that feelings manifest themselves in specific colors. His works also reflected his earnest study and interest in the era’s novel scientific and philosophical concepts.

My own work is less anchored in such scholarly or spiritual frameworks, at least not consciously so, while definitely echoing my qualms as to the human condition at large. I, too, regard color as not decorative or representational, even if my work is typically figurative, but rather as a means of intensifying introspective processes and encouraging contemplation.

Disclosure, 2020, Woodcut, rubbing, color pencil, on handmade Kozo and Abaca paper, 80 x 120 inches.

I do have a subjective color-correlated “emotional chart” (And I am not oblivious to common cultural and social color associations). Colors are present in a range of contexts in my works; a particular color can be of a figure, terrain, or sky; colors are printed, rubbed, or drawn. As my work has become increasingly multi-faceted, using colors extensively and expressively, the juxtapositioning of colors as well as media has become a key element in my creative process. The transitions and overlays of color in the composition are subtle yet essential in conveying concepts and emotions.

These processes and choices exceed formalistic statements. The expressive, nonrepresentational use of color and the delineating interlocking forms by color seek to enhance the sense of alienation and displacement, questioning the relationships within and between humankind and the natural world. Munch, the remarkable revolutionary artist, also viewed the seemingly irregular use of color as an act of looking beyond surfaces and recognizing the underlying instability of the world around us.

While Helen Frankenthaler is a formalist abstract artist and quite different from my figurative style, I have been inspired by her superior and intensely moving use of color, whether cleverly forming compositions or singularizing elements while evoking poignant emotions. The abundant skill, ingenuity, and profundity evident in her woodcut creative processes are truly stimulating, as I, too, constantly challenge myself thematically and formalistically, seeking innovative color use and media techniques.

While “Color is the first message”, a well-known quote by Helen Frankenthaler, may not necessarily be the primary attribute of my work, color has growingly become an integral and intuitive element. Challenging and accentuating contemplation in my commonly understated thematic “shorthand”.

Desolate, 2020, Woocut, rubbing, dry brush drawing, color pencil, on handmade Kozo and Abaca paper, 80 x 80 inches.

What are the direct references and aspects of history that your work includes?

History’s significance, influence, and inspiration are double, probably triple-fold, in my work and life.

As an individual and an artist, I am continuously concerned and preoccupied with the human condition, researching historical and current contexts and perspectives and questioning humans’ place and significance as part of their socio-political fabric and in the broader planetary scheme.

I am also frequently questioned as to the effect of growing up and working in Israel, characterized as an intensely politically, socially, and religiously charged environment, on my work. My personal background as the daughter of parents who are holocaust survivors, having escaped the catastrophe as young teens just in time, also has, even if a subdued presence, in many of my works.

Rumor, 2017, Woodcut, rubbing, ink, oil sticks, color pencils on handmade Kozo and Abaca paper, 65 x 120 inches.

For the most part, I consciously seek commonalities of experience that transcend nationalism and sectarianism through my art beyond my personal or historical circumstances. I lament the frequent loss of the necessary sense of responsibility towards our shared humanity as well as the lack of respect for the natural world that sustains us. My frequent depiction of isolated contemplative figures refers to the notion people have had to face social and humanistic challenges throughout history. We are, obviously, fundamentally influenced by social and political contexts, but the reality is that ultimately, the individual needs to make decisions, balancing apparent practical and specific dispositions with more complex moral parameters, and become responsible for any outcome of such decisions.

Historically, printmaking, specifically woodcutting, has been labeled the democratic medium because of its affordability and the freedom offered to the artist to work independently of patronage and church pressures and growing from middle age guild traditions. The humble origin of the board gave rise to the perceived humility of the woodcut process.

What began as an unsophisticated craft quickly blossomed into a major art form and one with sufficient power to challenge reigning doctrines and even make governments nervous. Undeniably, the emergence of freedom of speech and creative independence coupled with the inherent “mass communication” platform at the time. My enthrallment with woodcutting might have such subconscious historical socio-political roots. This certainly corresponds well with my predominant thematic and formalistic emphasis.

My work process to date is rather purist and fundamental. I draw and carve using multiple woodcut knives, using primarily pine wood panels. I embrace the knotty dialogue with pinewood as a form of collaboration and coexistence with natural elements. A dialogue requiring occasionally acceptable compromises on the one hand, producing stirring elements on the other.

I print my woodcuts by hand, rubbing the back of very large sheets of handmade paper with a wooden spoon, never using presses or assistants. Consequently, I can respond to the image as it evolves, adopting or enhancing unexpected textures, effectively drawing over the pre-carved wood panels as I print. Mastering woodcutting in itself, I also cherish printmaking’s essence, reusing my craved wood panels and figures in multiple different compositions, my own personal “vocabulary,” rephrased.

Transport, 2006, Transfer drawing monoptype and woodcut on paper, 38 x 50 inches.

Withdrawal, 2023, Marker drawing on pinewood panel, 23.6 x 80 inches.

I am drawn to and inspired by the great masters whose work focused on the human condition. Their brilliance exhibited not only in their tremendous talent and technique but also in their sensitivity to humanistic situations, frequently placing weak, desperate, and desolate individuals as the centerpieces of their works. Of the many great printmakers, several have been my “mentors’ and beacons of sorts in their breathtaking drawing skills and superb printmaking techniques, taking a stand and challenging the viewers, contemporaries, and themselves.

Rembrandt was considered a virtuoso printmaker even in his day. His work exhibited beyond sheer talent a sense of inventiveness and was such an acknowledged etcher, that critics were persuaded that he had discovered some secret process… Nonetheless, beyond my absolute admiration of his brilliance, I was struck by Rembrandt's sense of humanity. Rembrandt's depicted urban scenarios, as well as images of beggars and cripples, were respectful of the individuals, arousing a feeling of wrath at the plight of man, and it appeared he identified himself with them.

Francisco Goya, was a master working during a transitional period, regarded as an Old Master and as one of the first significant modern independent modern artists. Even his formally commissioned traditional dignitary portraits contained veiled criticism of the painted subjects. His etchings represented his unconditional opinion about the social and political circumstances of his times. A venerable, genuine, and harsh critic of his era…

Käthe Kollwitz. It is practically difficult for me to summarize in a few words the impact of Kollwitz’s personal journey and works on my own evolution as an artist. Working in the midst of the most dramatic socio-political times of the modern era, suffering and voicing the horrors of the two great wars. A woman who established herself in an art world dominated by men. In her own words: “I felt that I have no right to withdraw from the responsibility of being an advocate. It is my duty to voice the sufferings of men, the never-ending sufferings heaped mountain-high.”

Transient, 2021, Carved pinewood panels & hand printed woodcut, rubbing, pencil drawing, ink, on handmade Kozo & Abaca paper, 80 x 182 inches.

My work is rarely clearly contextualized or symbolically and thematically committed, reinforcing the drive to address a panoptic scope of the human condition. An inherent observation venue beyond geographical, political, or set chronological boundaries.

Most of the figures in my works appear contemporary, relatively composed, or displaying distress. Some are absorbed in a task, others pensive or observing; their disposition conveys a sense of expectation. They are habitually seemingly alienated from the surrounding landscape or recognizable chronology.

The inconsistencies, physical and temporal, aspire to enhance an overriding sense that the more momentous journey is the internal and introspective one rather than a particular contextualized occurrence.

A singular deviation from this very conscious thematic path is the precise historical reference in a couple of my woodcuts, Steadfastness (2010) and Time ... thou ceaseless lackey to eternity (2017).

The rubble-banked building façade perched on higher ground was inspired by a 1944 photo of the sole remaining wall of the historic New Synagogue in the Czech town of Holešov, burned by the Nazis in 1942. My mother (now 99), living in Israel, was the only Jewish child from Holešov to escape the Nazi occupation, deportation, and concentration camps that murdered all but about 15 Jewish citizens.

Time ... thou ceaseless lackey to eternity, 2017, Hand printed woodcut, rubbing, grease pencil, ink, on handmade Kozo & Abaca paper, 80” x 182”, 200 x 400 cm.

“The inconsistencies, physical and temporal, aspire to enhance an overriding sense that the more momentous journey is the internal and introspective one rather than a particular contextualized occurrence.”

Subterranean, 2020, Woodcut, rubbing, color pencil, on handmade Kozo and Abaca paper, 80 x 80 inches.